Great Hymns: Secret Sauce of the Protestant Church

The church hymn built English-speaking Christianity. It's time to revive this discarded tradition, making these old favorites a part of regular worship again.

The decline of mainline Protestant churches cannot be traced to a single cause. Faced with shifts in demographics, immigration, theology and culture, thousands of churches have closed, at what is now an alarming pace. Among the unfortunate and unnecessary casualties in this period has been the abandonment of traditional church worship, including the hymn. Hymn singing was once the lifeblood of Protestant worship, a communal experience that unified congregations and reinforced theological identity, especially in Anglican, Methodist and Congregational churches, which perfected the practice. That tradition is now disappearing.

I grew up hymn singing at a busy Episcopal Church in Virginia Beach in the 1970s. This was before 1979, when the “Holy Eucharist” (the renamed Holy Communion) arrived as the weekly service, and the church stopped saying Morning Prayer. Morning Prayer had been filled with hymns, sometimes as many as five. From singing in the choir, I learned the tunes, and the drill of them, over and over. That church, Eastern Shore Chapel, had a longstanding choir tradition; we played and sang in the church’s loft, leading the congregation from high, in the back.

Like the old language of the Book of Common Prayer, now mostly jettisoned, we took the hymns for granted. We did not then know we were being taught a tradition that could slip away, or be thrown out, like an old vinyl record, in the name of church growth and liturgical renewal.

Today, most evangelical churches offer congregations a few Christian radio songs, to start worship, and then follow it with a long sermon. It’s all about performance, and creating a mood. The music is concert style, and watched. This is done in order to attract newcomers. To start the service, the lights go down, like a rock concert. The music is not about the congregation amending its life, but attracting the guest to the message of the preacher. In these churches, the men almost always look uncomfortable singing, even as they are happy to sing at a baseball game.

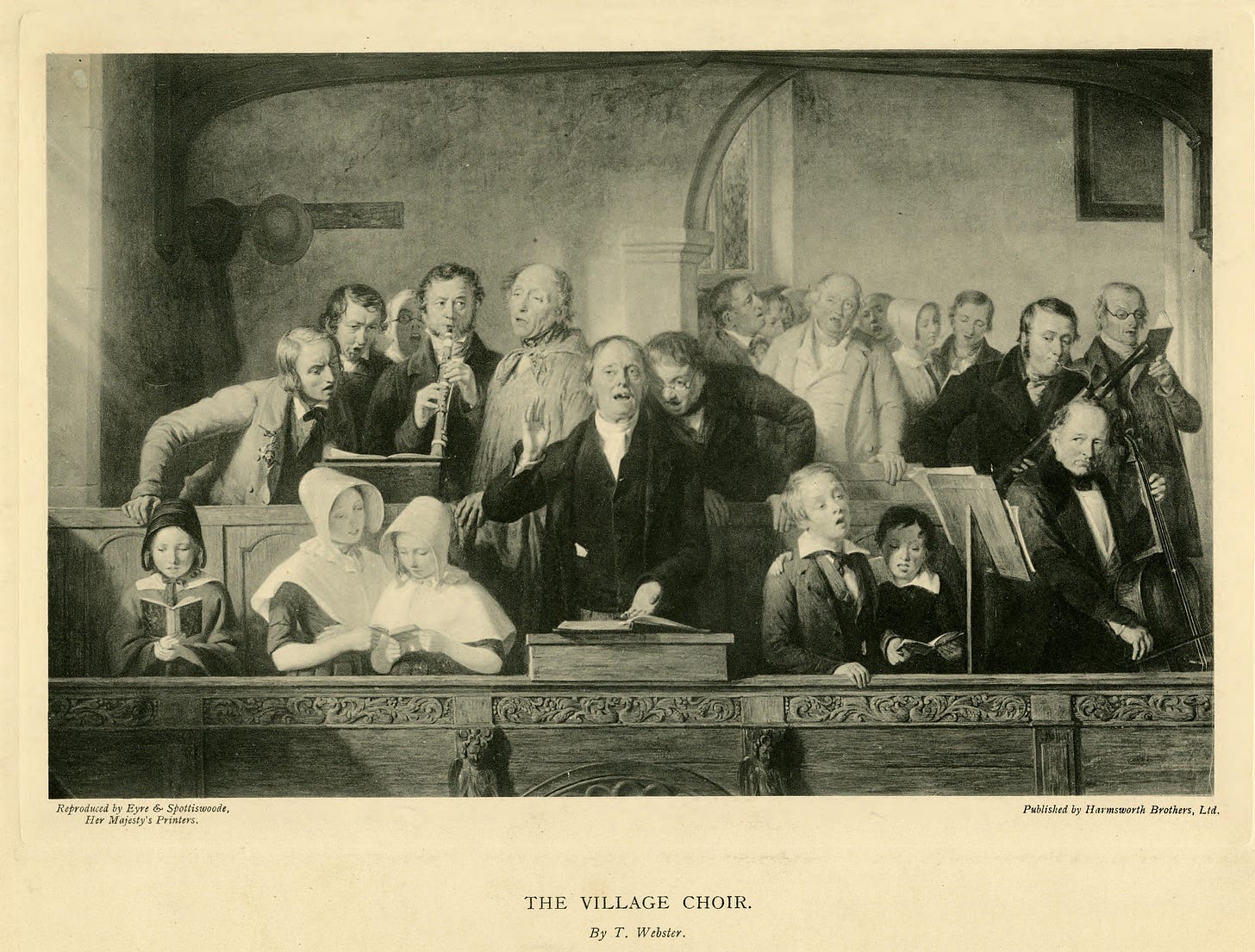

As churches switched formats like radio stations, they called the change the worship wars. Worship wars are not new. In Anglican church history, I came across an 1874 letter to the editor to the English weekly, The Choir. It tried to sort out how “unison” singing had eclipsed “harmony” singing, which was much more sophisticated. What was telling about the exchange is not only the depth of the argument, but that there was an entire weekly newspaper dedicated to singing this music. It even published notes from upcoming Sunday bulletins, a sort of “What’s On” magazine of upcoming concerts and hymns.

The late Martyn Lloyd-Jones (1899-1991), a Wales-born evangelist, was suspicious of any “performance” aspect of music in the church, even as his Westminster Chapel had a notable Henry Willis organ, and he quoted hymn verses in many of his sermons. He said in a sermon, “The ideal is that all of the people should be lifting up their voices and rejoicing as they do so. The ideal is a people, a congregation, singing the praises of God together. And the only use of an organ is to accompany that.”

Lloyd-Jones was also adamant that every member of the choir should be of Christian character and have a love of the truth and “the delight in singing it.”

I spent a decade on the staff of the Episcopal Diocese of Southwest Florida observing its churches. I came to realize that all the well-attended Anglican churches that I visited sang hymns the old way. The churches that were struggling were the ones that had the music all muddled up, and sang frightening folk songs from the 1970s, calling it “contemporary” worship. The state of the hymn was not only an illness, but a symptom.

Clergy, lay leaders and choir directors need to have a conversation. They can make it all work again. A Reddit user put it well, saying that for the Episcopal Church, its preservation of hymns “will be the last part of their church that will remain as all the rest of it crumbles around them (no offence).”

As the art of hymn singing is being lost, many nuances have been forgotten by most of us sitting in the pews. I thought it was time to list some of the essential parts of our tradition; some are obvious, others forgotten.

Some essentials:

Use the Favorites

The habit of using traditional hymns is so diminished that if you sing “The Church’s One Foundation” or “Our God Our Help in Ages Past” or “A Mighty Fortress” a few times a year, you are keeping it in the canon. Church attendance is so sporadic that it won’t be repetitive. It would be nice to ease up on the classics, and try lots of newer hymns, but the Protestant church world is fragile, and the core canon of hymns needs attention before we lose the tradition altogether. Below, even Prince Harry will sing during “Praise to the Lord Almighty.”

Play the First Verse Instrumentally

The congregation needs to hear the tune, and the key. Even older members of the congregation need refreshing. The playing of the first verse (instead of an intro) also gives the congregation the time to start looking at the words, and getting prepared to sing. If congregations can also be encouraged to use the hymnal, they will see the notes with the song, where the song starts, and how the notes go up and down. Here, a version of “Ye Holy Angels Bright” from New York’s St. Bart’s.

Refrain (Mostly) from Refrains

A pop song, with a refrain, does not always provide the variety needed for congregational singing. My church, with its old rector, had an unfortunate habit of singing Taize songs. These sorts of songs, often brought over from Cursillo or other spiritual retreats, seem to be about recreating a person’s previous moment of personal spiritual happiness, and not about bringing the congregation together. There are always exceptions; “How Great Thou Art” is one. Below, a Matt Redmon version.

Sing All the Verses

Some churches will skip verses, to shorten the song. That is wrong. Singing all the verses is not just about the words; the congregation better learns the tune each time the verse is sung. If you skip verses, you aren’t having enough time to practice the tune. Boca Grande United Methodist always sings all the verses; the staff reminds that each hymn is a poem, as well as a song, and meaning is lost if you cut out the middle.

Avoid Christian Radio Tunes

Contemporary Christian Music is designed to be performed, to an audience. Watch the audience in a mega-church; most of the songs are not singable by the congregation. The song succeeds or fails on the strength of the band, and their musicianship and voice. That is not to say that the choir cannot try all sorts of new songs during the offertory or communion. There are ample opportunities. Many of these songs are wonderful anthems, or preludes, but they are not hymns.

Lose the Tokenism

Spirituals sung during Black History Month almost always fall flat in a white congregation. That is an observation, not a judgment. There is also a cultural aspect missing. Asking a tired old group of 70-year-old Protestants to sing “Soon and Very Soon” or “There’s a Sweet Sweet Spirit” and it almost always falls flat, doing no credit to the song or its legacy. It just feels, and is, cringe. And realistically in the 20th century, black Episcopal churches and Anglo-Caribbean churches all sang traditional hymns. “Abide with Me” was a favorite hymn of Gandhi. Here, at a military Beating Retreat in New Delhi, is Bapu’s favorite song. Unbeatable.

Teach children hymns, not hand gestures

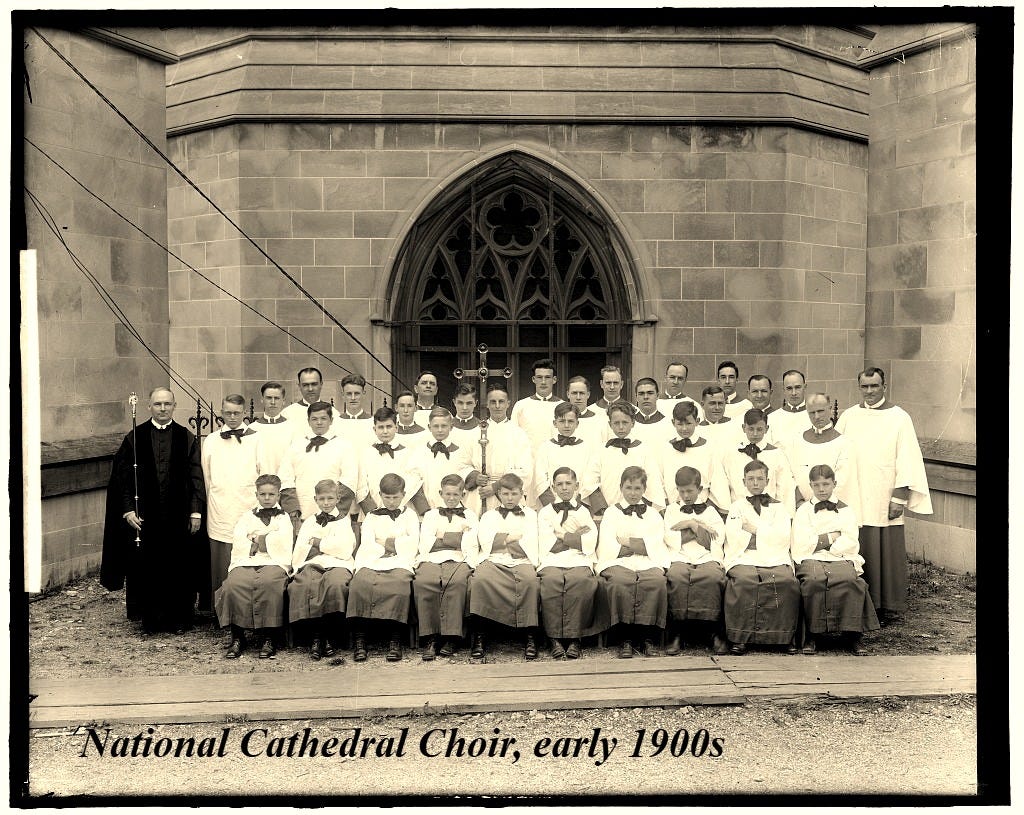

Often, kids are often taught musical gimmicks like silly songs or hand gestures, something music teachers and Vacation Bible School leaders seem to be obsessed with. That is for toddlers, not first graders. Much has been made of the importance of the musical training of the African-American church; what is forgotten is that the entire nation of Britain during most of the 20th century was also singing hymns every week, providing a base for the British music invasion of the 1960s. Today, a children’s choir can provide voice training, group music skills and moral instruction to members of the community, and make the choir a public offering.

Keep the Hymnal

While most cannot read music, the average person can understand the ups and downs of notes, and can easily see if they are quarter notes, half notes, etc. Most hymns are syllabic, in that there is one note per syllable, which makes it easy to understand. When there is a hymn like “For the beauty of the earth,” and the “the” takes two syllables, you can see the notation. Church bulletin software often prints the lyrics, however.

Romp Through It

Occasional difficult hymns keep things interesting. At Sarasota’s Church of the Redeemer, Choirmaster Anne Stephenson-Moe would use the few minutes before the service to go over new canticles, to teach them to the congregation. A Reddit post on unfamiliar hymns supported trying out new hymns and difficult music, calling it “Romp through it.”

Change It Up

The AABA of a familiar hymn is tonic to the singer. The late Matthew W. Bassford, a scholar of hymns, explained the specifics. “Musicians often don’t like rounded-bar tunes. They’re bored by them. You sing the same thing over and over and over again. Yawn. However, what seems like a stumbling block to the musician is a blessing to the congregation.”

A skilled organist will use the last verse of the familiar hymn to reharmonize, basically keeping the melody, but offering a new take. During the last hymn of the service, this is particularly effective, and pleasing to the congregation, which gets to hear the familiar in a new way. Below, take a listen to Philip Eyrich at Lighthouse United Methodist, and note his transition before the last verse. His skill is emphasized by the enthusiasm of the congregation’s signing, which responds.

Bring Back the Amens

The Episcopal Church’s 1940 Hymnal had an “Amen” at the end every song, a practice encouraged in 1881, with the publication of “Hymns Ancient and Modern”. The Amen was eliminated in the Episcopal 1982 Hymnal. The Amen closes the song, and gives the congregation an ending to the thoughts in the hymn. The Amen was removed from the Methodist hymnal in 1989, on the recommendation of Carlton Young. While bringing back the Amen should not be the first course in reviving hymns, it is important to note it is one of the missing elements from the hymn’s heyday. Sarasota’s Church of the Redeemer, an exemplar church in boisterous hymn singing, does not sing them. However, Coral Ridge Presbyterian in Fort Lauderdale, which almost jettisoned its traditional worship but brought it back, does sing the Amen.

Pace the Songs

Some churches play songs in dirge-like speed, and it is awful. Some now say that an organ makes them sad. The old Episcopal 1940 Hymnal had a reference for each song as to how each would be sung. “Stand up for Jesus” was described as with stately dignity. “Onward Christian Soldiers” was described as in march time. Other descriptors included in moderate time, with tranquility, slow with serenity, quietly, and joyfully with dignity. Without those directions, and without practice, many organists and choirmasters have lost the skill of how to pace the song properly. In addition, the same hymn sung in an echoing stone cathedral should not be same tempo as in a small wooden church, or a newer church with carpeting. Dr. Lloyd-Jones put it well in one of his speeches, saying that, “The organist is in a position to control the praise so much. He with this powerful instrument can control the rate at which you sing and that can greatly affect he hymn.” Here, good pacing at St. John’s, Detroit.

Turn Mics Off, No Guitars

Clergy are almost always using microphones. If they sing during hymns, they ruin the group sound. The congregation is listening for the others in the church, near them, and how to match. (Also, clergy need to hide their guitars, and not inflict it on congregations. There, I said it.)

Keep Thee and Thou

Chris Rice’s “How Great Thou Art” has 41 million views; the comments after the song are indicative of what the words mean to people. This is not outmoded language. Hymns do not need to be sanitized, either. Hymns were once under the categories such as church penitent, church militant and church triumphant. They are metaphor. The term "church militant" refers to the Christian church on earth, actively engaged in a spiritual battle against sin, evil, and temptation. It contrasts with the "church triumphant," which represents the faithful in heaven. The 1970s idea that “Onward Christian Soldiers” is somehow militaristic or pro-war, and cannot be sung, or needs its words to changed. It is yet one more way clergy have alienated their base by hiding from these songs.

Start With Christmas

There are real disagreements in Protestant theology. But traditional church music is one place that almost all can come together. For the people who are not interested in church at all, the Christmas carol, or hymn, is also a unifying force. Even Jewish singers, or non believers, will sing traditional Christmas hymns as a cultural artifact larger than religion.

What is the way forward? Backwards.

In the early 20th Century, Ralph Vaughan Williams helped to rebuild church worship in the Anglican communion, as did Bland Tucker in the late 20th in the U.S. New leaders are needed. The Mormon Church has been a standout in preserving and claiming the hymn tradition through the Tabernacle Choir; they continue to grow as a denomination.

There is a future in hymns; even in the de-Christianized U.K., church choirs are a staple of TV talent shows. Thomas Hewitt Jones has new hymns with the Royal School of Church Music. Ed Sheeran, who grew up in a choir, has helped a church choir in Ipswich parish, St. Mary le Tower.

I will leave the reader with a Shane & Shane arrangement of “Come Thou Fount” as part of the American church music effort called The Worship Initiative. There is plenty of life left in these vintage songs; this is an 18th century classic, written by in England by Robert Robertson (1735-1790). Shane & Shane has 9.3 million views. Who doesn’t want to sing along to this?

Very nicely written, Garland, and quite a scholarly piece really. I have forwarded it to a few friends who know more about the subject than I do.

You bring to mind my youth growing up in Virginia Beach as well, but going to Galilee Episcopal Church. Where my mother often played the organ. From her I get much of my love of music.

I agree with you that we don’t need songs that need to be performed to an audience; we need songs that are to be sung together, to bring the congregation together.

But my unscholarly criticism of the lot of the old hymns is that they iften do not have very good tunes. Traditional English or Irish folk songs usually have great melodies that carry themselves along. Traditional hymns to me often lurch from one place to another without purpose, with some big exceptions, of course.

Thanks again Garland for such an insightful and timely post. I always try to attend Christmas services especially for the carols. The stuff on radio really has nothing to do with the true meaning of Christmas. For that matter neither do most TV specials, which is why I tear up every time I hear Linus cite scripture when Charlie Brown asks if any knows what Christmas is all about.

I’m afraid the rest of the year has become banal in church music and church practice. As someone who grew up Baptist and later became high church I enjoy the symbolism and self examination and reflection on Christ and what He did for us as expressed in the ancient methods, buildings and art. This summer I continued to retreat into those methods after finding out the man who wrote A Mighty Fortress is my uncle 15 generations back.